History

A 4-month-old female Pit Bull was referred to Animal Imaging for a (TSPS) to determine if the patient had a portosystemic shunt, which was suspected by the referring veterinarian based on the history and clinical exam findings. Clinically, the patient had an altered mentation and was having seizures. The serum chemistry revealed a mild hypoproteinemia (4.7 mg/dL) and elevated liver enzymes (AST 98 U/L, ALT 180 U/L and ALP 198 U/I). The CBC was within normal limits. Pre and post-prandial bile acids were also submitted and found to be elevated (Pre 38.1 umol/L and Post 231.6 umol/L).

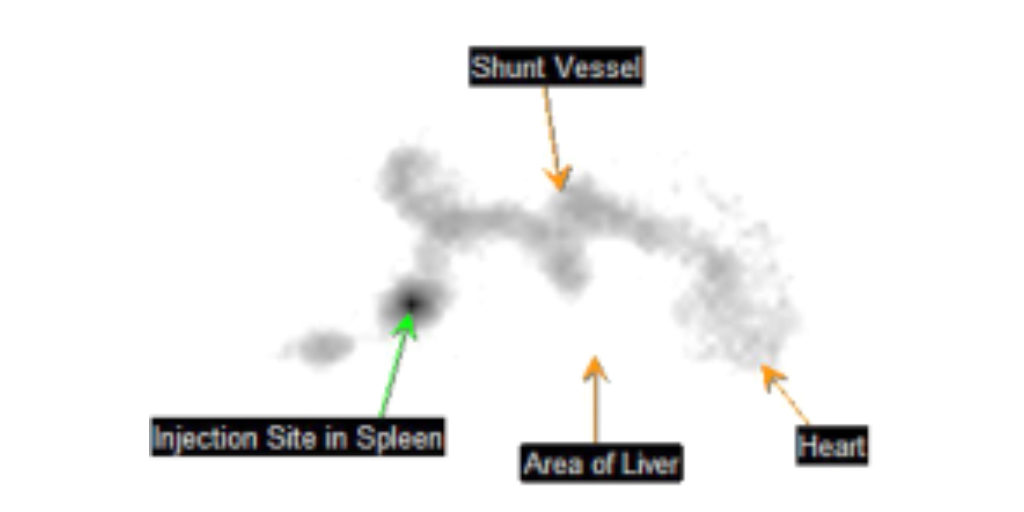

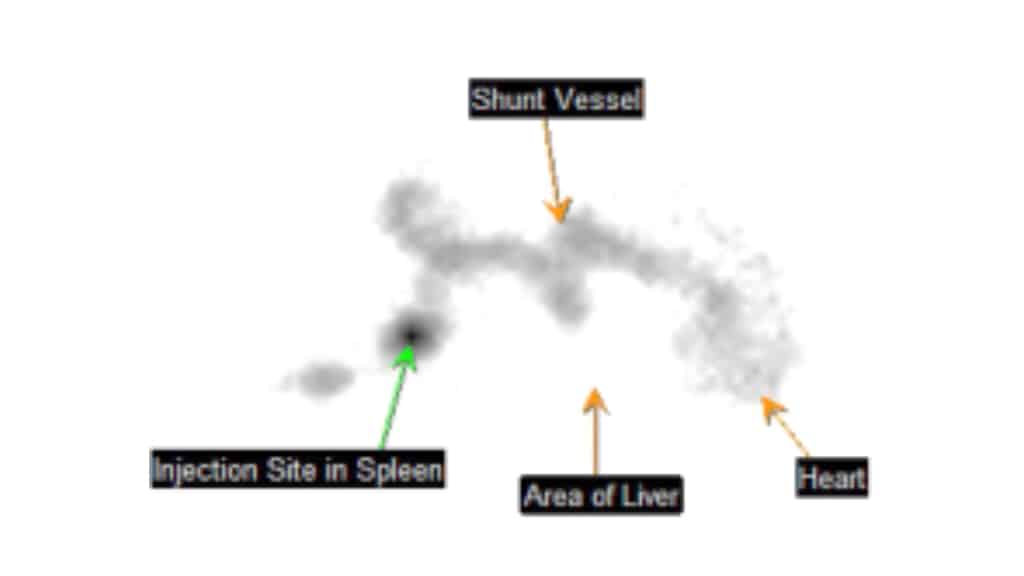

At Animal Imaging, our standard examination protocol for potential portosystemic shunts begins with the scintigraphy study. For the procedure, the patient is anesthetized and a small volume of radionuclide (sodium 99mTc-pertechnetate) is injected into the spleen using ultrasound guidance. The injection is performed with the patient in lateral recumbency on a gamma camera, so the radioactivity can be traced as it moves from the splenic venous sinusoids into the splenic vein and then into the portal vein. In a normal animal, the radioactivity should flow from the portal vein into the liver and then eventually circulate into the heart. A positive or abnormal TSPS identifies blood flow from the spleen which bypasses the liver via a shunting vessel and goes directly to the heart. These abnormal shunting vessels can commonly be visualized on the scan.

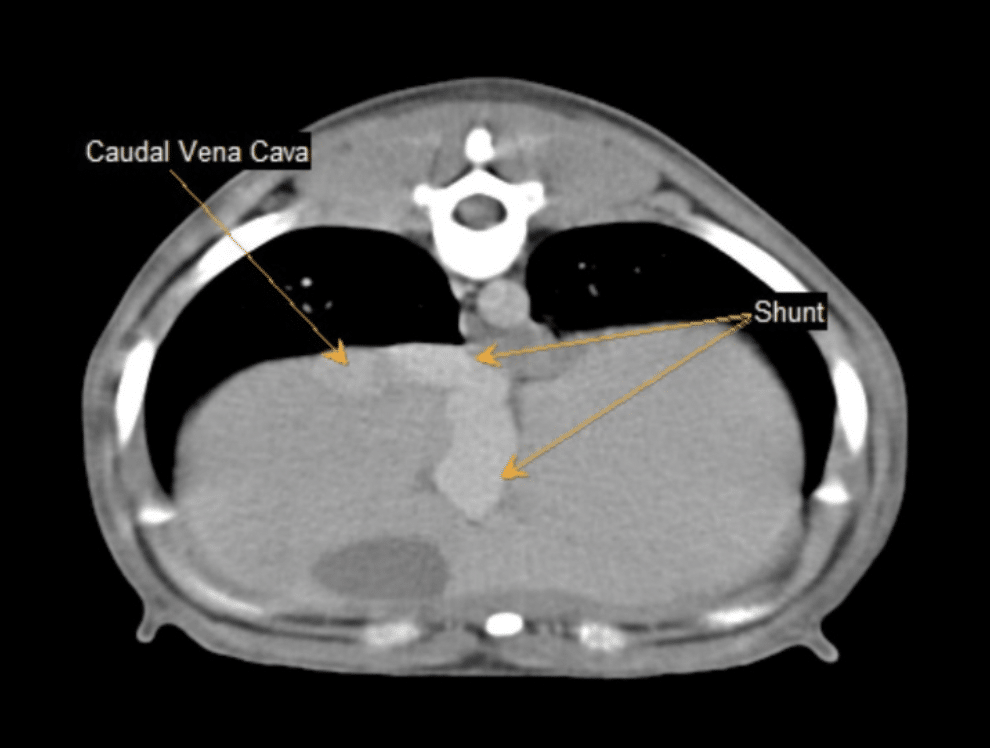

At Animal Imaging, if the scintigraphy study is abnormal, an abdominal CT with contrast is pursued for additional anatomic information about the shunt(s), particularly to aid in surgical planning. The CT will also help to assess additional intra-abdominal structures, such as the liver, kidneys, and the urinary bladder. In the event of a negative TSPS exam (no shunt found via scintigraphy), an abdominal ultrasound is then performed, looking for evidence of any other disease processes that may be causing the clinical signs and/or biochemical abnormalities. Also, of note, a normal TSPS study does not exclude the possibility of microscopic shunting (i.e. microvascular dysplasia). A liver biopsy would be needed to make this diagnosis and may be recommended if a definitive cause of the clinical signs and biochemical abnormalities is not identified on the imaging performed.

Portosystemic shunts (PSS) are abnormal vascular communications between the portal vein and systemic circulation and may be categorized as either congenital or acquired shunts. Congenital PSS are often a solitary or single shunting vessel and can be either extrahepatic (most common type, usually seen in small breed dogs) or intrahepatic (more common in large breed dogs) in location. Acquired shunts typically develop secondary to end-stage liver disease/cirrhosis and/or chronic portal hypertension. These shunts usually consist of multiple small, tortuous vessels, often found caudal to the kidneys within the retroperitoneum.

On the TSPS study of this patient, the bolus of radioactivity coursed from the spleen, through the splenic vein, into the portal vein and into a shunting vessel. This vessel looped dorsally and cranially entering the heart caudally, in the location of the caudal vena cava. Blood then circulated into the systemic circulation. Due to the positive TSPS, the patient remained under general anesthesia and an abdominal CT was performed.

In the images above, the bolus of radioactivity within the shunting vessel courses straight to the heart in the abnormal case, while the radioactivity is visualized within the liver before circulating to the heart in the normal animal.

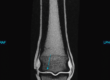

On the CT examination, a solitary, large intra-hepatic shunting vessel was identified, extending from the porta hepatis, through the liver and into the caudal vena cava, at the level of the diaphragm. The location and course of this shunt was most consistent with a left divisional shunt or patent ductus venosus (PDV), which is the most common type of intrahepatic shunt. The liver was also small in size, which is a common secondary finding in cases of portosystemic shunts.

Treatment options for congenital portosystemic shunts include medical management and/or surgical correction. Surgical correction (attenuating/narrowing or ligating/tying off the shunt vessel) is often the best option for congenital PSS, especially if the shunt is a solitary vessel, no evidence of portal hypertension or secondary acquired shunts are identified, and the patient is young. The goal of surgical correction is to slowly re-route the blood from the shunting vessel back into the portal vein and into the liver. This enables the liver to appropriately “filter” and remove the toxins/compounds from the blood drained by the portal vein prior to entering the systemic circulation. If surgical correction cannot be pursued due to financial constraints or the patient is not a good surgical candidate, medical management can be used to improve clinical signs and quality of life. Medical management may include medications to decrease the number of toxins produced by bacteria in the colon, anti-seizure medications and/or dietary modifications (restricted protein)

Comments

This patient was referred to a veterinary surgeon for surgical correction of the shunt. A transvenous embolization was performed, which places an embolization coil into the shunting vessel with the guidance of fluoroscopy. This technique allows the shunt to close progressively over time, minimizing the risk of development of acute portal hypertension. The patient reportedly is doing well after the procedure with no postoperative complications.